Bridging The Microfinance Gap For Smallholder Farmers

Stephanie Hanson is senior vice president of policy and partnerships at One Acre Fund. A version of this blog was originally published by This is Africa, a publication of Financial Times Ltd. Click here to view the original post.

Microfinance is widely known for the incredible speed with which it has scaled to reach hundreds of millions of people, and the positive effect it has had in reducing poverty.

However, what many people do not know is that most of these microfinance institutions are located in urban and suburban areas, and they largely target the urban and suburban poor. As a result, the largest group of poor people in the world - smallholder farmers - are largely financially excluded.

While 55 percent of Africa’s population is engaged in agricultural livelihoods, only approximately 1 percent of bank lending across the continent goes to the agricultural sector. In sub-Saharan Africa, 38 percent of adults living in cities report having a formal bank account, compared with only 21 percent of adults living in rural areas.

Smallholder farmers represent two tremendous opportunities: a market opportunity for any financial institution looking to grow their client base, and an impact opportunity for all financial institutions that have a social mission. The total amount of debt financing available to smallholder farmers in the developing world is approximately $9bn. This amount meets less than 3 percent of the estimated total smallholder financing demand, which is calculated to be $450bn globally.

Farmers comprise the largest and poorest group at the bottom of the pyramid, so financial tools for farmers have very high impact potential. Sustained growth in the agriculture sector has proven 2 to 4 times more effective at reducing poverty and improving livelihoods than growth in other sectors. Recent research shows this can be as high as 11 times in sub-Saharan Africa.The uniform profession of farmers also means that providing financial services to farmers is a highly replicable business.

Perceived risk and lack of expertise are the most significant reasons that more banks and microfinance institutions have not yet started offering agriculture finance products. Compared to urban lending, which microfinance institutions are familiar with and have developed expertise in, rural lending feels quite risky. Most banks and microfinance institutions do not have internal expertise on agriculture, and are unsure how to structure loan products that would both meet the needs of farmers and mitigate the risk they take on by lending to them.

Further, operating in rural areas poses infrastructural and logistical challenges. Margins will be lower than when serving urban clients, and financial institutions will have to build out either physical or human infrastructure to reach remote rural areas. Currently, significant distances between bank branches represent a major barrier to rural financial inclusion. For example, in Tanzania, where there are less than 0.5 bank branches per thousand square kilometers, 47 percent of all unbanked persons cite distance from a bank as a primary reason for not having an account.

There is a small but growing movement of financial institutions that have figured out how to overcome these challenges and lend to smallholder farmers. Institutions like Opportunity International, Vision Fund, Microensure, as well as One Acre Fund, all offer products to smallholder farmers that successfully address their financial needs.

The Initiative for Smallholder Finance recently published a briefing on direct-to-smallholder finance in which they note that over 150 finance providers currently offer direct-to-farmer finance. To help facilitate the entry of more financial institutions into the sector, the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) is conducting research to better understand the financial needs of smallholder farm families.

Through our work at One Acre Fund, we have discovered some basic principles that reduce the risk of lending to smallholder farmers, while increasing the income impact that those farmers realise from their loans. We currently serve 200,000 smallholder farmers in East Africa, and have a repayment rate of 98 percent.

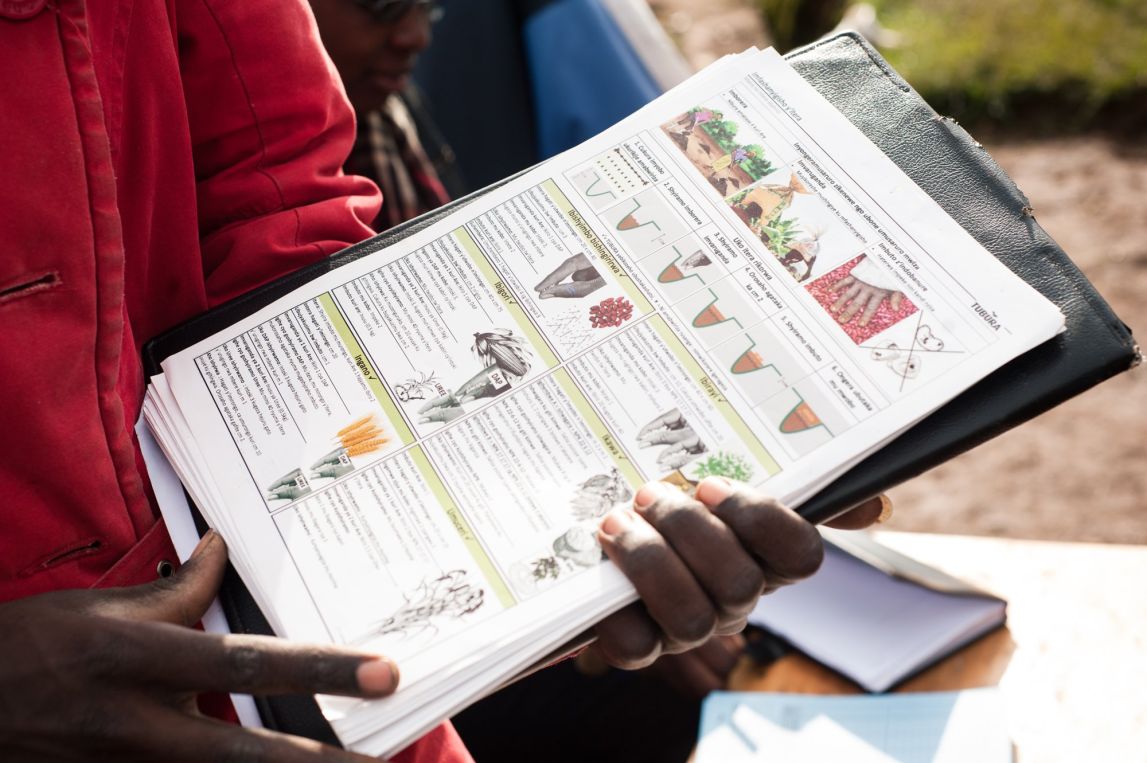

We have found that lending to farmers is most effective when we lend seed and fertiliser instead of cash. Providing assets to farmers ensures that the loan is utilised for the intended purpose, and overcomes the challenge of limited access to seed and fertiliser close to the homes of our clients. We also offer a completely flexible repayment schedule to accommodate the irregular cash flow of most smallholder farmers.

Finally, we pair our loans with agriculture trainings, so that farmers can maximise the income impact of the seed and fertiliser that they use. These principles allow our clients to see at least a 50 percent increase in farm income per acre, as well as ensuring that One Acre Fund is repaid.

One Acre Fund is just one of a small number of organisations that has figured out how to successfully lend to smallholder farmers. With a global financing gap of $441bn, we need thousands of financial institutions to step in and start serving this market. Farmers are 70 percent of the world’s poor. Agriculture microfinance is our best tool to significantly reduce global poverty - and it is also a promising business opportunity.