What to Read on Agriculture Microfinance

Microfinance and Rural Farming Communities

This article was originally published on the Financial Access Initiative blog.

The majority of the world’s poor share one profession: farming. Most of these farmers cultivate less than 10 acres of land, far away from paved roads and with limited access to the improved seed and fertilizer they need to produce good harvests. Most of these farmers also lack access to financial services that could help them buy that seed and fertilizer. If the global microfinance industry seeks to have a long-term impact on global poverty, it must address the needs of smallholder farmers. Most microfinance institutions are focused in urban and peri-urban areas, but a few are starting to offer products specifically targeted at farmers.

We’ve seen fast-growing interest in the farm microfinance sector in the last few years. The books, videos, and papers discussed below helped us understand the market opportunity in farm microfinance, and what needs to happen for the market to take off.

Financing Farmers is Important

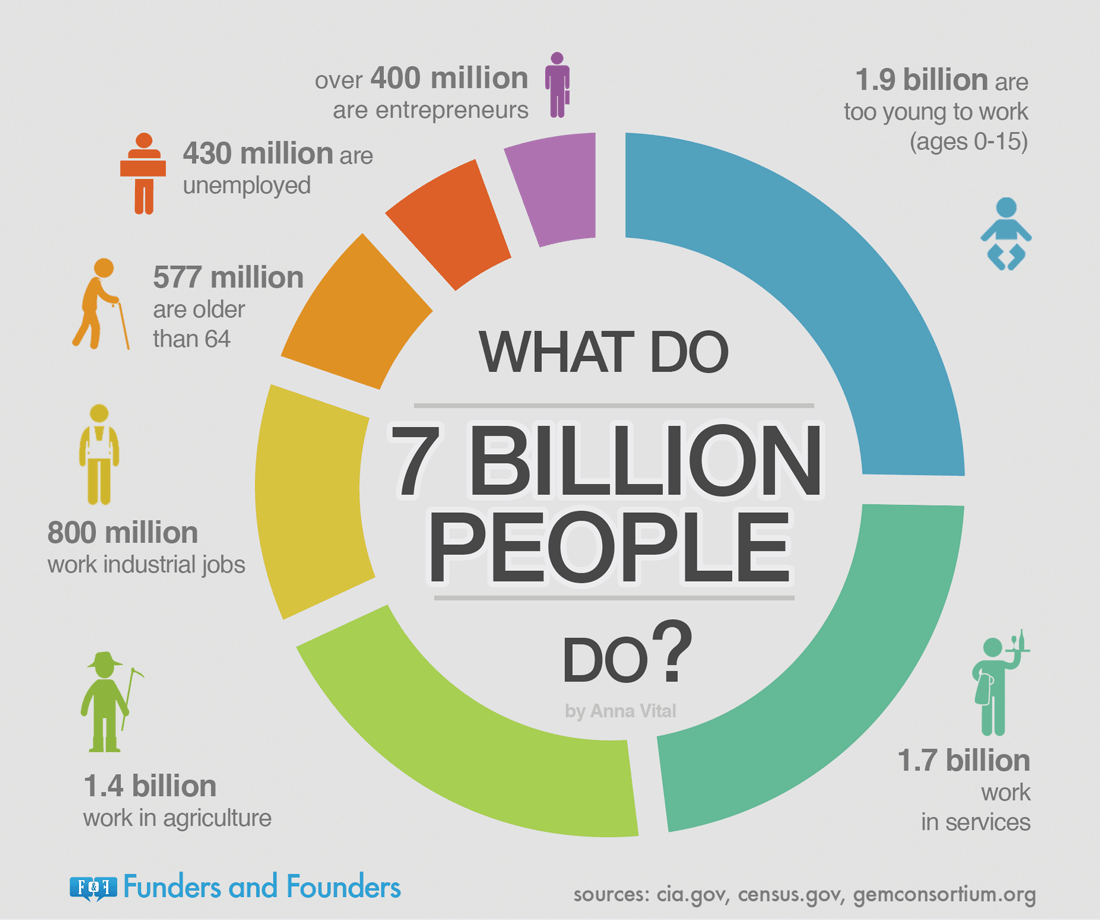

The World Bank estimates that agricultural development is “two to four times more effective in raising incomes among the very poor than growth in other sectors.” Not only is this a high-impact sector, it’s also a large one. Farmers account for more than 30% of the global working-age population, and most of them live in poor countries.

For a vivid portrayal of what happens when smallholder farmers can’t access the resources they need, read The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind. This memoir, written by William Kamkwamba and journalist Bryan Mealer, paints an honest picture of Kamkwamba’s family and their collective anxiety as they struggle to get through a terrible farming season in Malawi. Their “hunger season” that year was not unique. The majority of the country faced the same problem, as did millions of farmers across the region.

What is striking in Kamkwamba’s book is the ripple effect of this problem. Kwamkamba is hungry, so he can’t work a full day in the field and is less productive. At the local market, there are rapid price increases. Through the country, there are rising social tensions, public unrest, and violence.

Fortunately, it’s completely possible for farmers like the Kamkwamba family to significantly increase their agriculture productivity in just one season, creating a ripple effect of income generation throughout rural communities. We’ve experienced firsthand the impact of agriculture development through our work at One Acre Fund. Reading Roger Thurow’s book The Last Hunger Season is the closest thing to spending days out in the field learning from farmers. It follows four Kenyan farmers over the course of a year as they work to increase their incomes and provide for their children (he also speaks passionately on the subject in this TEDx talk). All four farmers are customers of One Acre Fund, which provides them (and 180,000 other smallholder farmers in East Africa) with seed-and-fertilizer loans and training.

Both books illustrate that the challenges faced by smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa are surmountable, and that farm microfinance is essential to catalyzing agriculture development. Perhaps the biggest barrier holding MFIs back from meeting that demand is perceived risk.

Financing Farmers Poses a Risk, But It Can be Mitigated

Agriculture is often perceived as much riskier than other sectors, particularly by financial institutions that lack in-house expertise on agriculture. This lack of understanding leads many MFIs to inflate the risk of farm microfinance. Financing farmers presents risks that vary in both likelihood and severity, but they are identifiable and possible to mitigate effectively.

In a 2005 CGAP paper, Robert Peck Christen and Douglas Pearce outline ten practical strategies that can help reduce the risk of an agricultural finance product. In our experience, the most salient risk-related features they discuss are covariate risk, credit risk, and production risk.

Risk in agricultural lending is often covariate. Weather and crop disease problems can devastate yields, and they generally affect many clients, not just one. The paper proposes diversifying a loan portfolio across geographical areas, crops, and types of livestock. It also suggests pairing loans with index-based insurance to protect against the most extreme cases of weather- or disease-related crop loss.

Loan terms tailored to growing seasons and flexible repayment schedules help manage credit risk. Lenders need to accommodate the “cyclical cash flows and bulky investments” of farmers. Successful models build repayment requirements around the cash needs of farmers without compromising “the essential principle that repayment is expected, regardless of the success or failure” of the farm. For instance, farm microfinance products often have terms that are tailored to the agriculture season and offer flexible repayment schedules instead of strict weekly or monthly payments.

Production risk can be mitigated by bundling lending with access to inputs and training. If a farmer is given a cash loan and uses it to buy low-quality seed or fertilizer, her production will suffer. Lenders can eliminate this risk by bundling loans with access to inputs and training. They can use contractual arrangements with agrodealers and extension workers to guarantee input quality and access to training, or they can provide these services using their own resources and staff.

If financial institutions utilize the strategies above, agriculture risk is manageable.

Farm Financing Must Be Bundled With or Linked to Other Services

Examples of successful farm microfinance invariably do more than just provide finance. If a farmer doesn’t know the proper planting technique for a crop, a cash loan is useless. If a farmer produces a great harvest, but can’t store it correctly or sell it for a good price at the market, she can’t generate increased income. Smallholder farmers need access to all parts of the value chain—farm inputs, financing, training, and markets. Successful farm microfinance products address the entire value chain for a smallholder farmer.

This principle is best articulated by Ugandan grain trader (turned agriculture financier) John Magnay. He argues that MFIs must have a “clear understanding that microfinance is just one of the stakeholders within the rural model.” He acknowledges the interdependence of the agriculture model and recommends a two-pronged strategy: monitor household cash flow, and manage the value chain.

If an MFI takes more control of the value chain, it puts more at stake for the organization, and acts as a strong incentive to “get the approach right.” Magnay recommends linking into agribusiness and providing agriculture trainings to maximize yield. One Acre Fund has found that it’s especially important to provide farmers with high-quality seed and fertilizer.

The channels for delivering this strong control over a value chain vary significantly, and the extent to which a specific MFI controls or partners with others in the value chain will differ. This is a very different way of doing business for most MFIs, and for the farm microfinance sector to grow, MFIs will need to adapt. Are there structures in place to facilitate this?

Farm Finance Needs to Crowd-In Key Players

There is an enormous market of customers for farm microfinance products, and only a handful of institutions serving them. This Dalberg report sizes the market demand for smallholder agriculture finance at $450 billion, most of which is unmet. To meet even a fraction of this demand, we need lots of MFIs to develop new products and deliver them to their customer bases at scale.

In this presentation, Willy Foote, founder and CEO of Root Capital, speaks about their inspiring approach of “Finance, Advise, Catalyze.” Root Capital is an agriculture finance lender, but they also provide financial training to their clients so that they can grow their businesses. Finally, they seek to grow the entire market for agriculture finance by collaborating with peer organizations. They recently helped launch the Council on Smallholder Agriculture Finance, an alliance of social lending businesses that targets “the missing middle,” businesses that require financing of $25,000-$2 million.

Key players in farm microfinance need to share more knowledge with other practitioners to establish best practices that others can follow. Much like Root Capital is actively trying to crowd-in more competition to the “missing middle,” One Acre Fund seeks to attract more players to farm microfinance, the sector that serves the poorest smallholder farmers in the world. Collaborating with other practitioners, we aim to help MFIs develop farm microfinance products that can address some of the enormous unmet demand in the sector. This is our best bet to spur global agriculture development, and to have a long-term impact on global poverty.

Stephanie Hanson is senior vice president of policy and partnerships at One Acre Fund, and Mike Warmington is microfinance partnerships manager at One Acre Fund.